News: Cutting agricultural aid research or how to dig your own grave...

Giving people fish or teaching them to fish?

A few years back, I had a meeting with Sheikh Mohammed bin Rashid Al Maktoum, the Ruler of Dubai, Prime Minister and Vice President of the UAE.

I told him of the humanitarian work we did. He listened attentively, and kept a silence after my explanation. Then he said candidly: "You know, you are giving people fish, instead of teaching them how to fish. Give a person a fish and he will eat for a day, teach him how to fish and he will have food for the rest of his life!" I was quick to respond: "Your Highness, when people are starving, they are not interested in being taught how to fish. If we give them fishlings for their pond, they will eat it, rather using them for breeding. Our organisation gives people the fish, so they are not starving anymore, and have the energy to be taught how to fish, and to fish themselves. Other organisations we work closely with, teach them how to fish, how to breed fishlings. After that, others come in and teach them not to overfish their pond, or even to market their excess harvest, set up funding mechanisms to sell their harvest beyond their own village. We all work hand in hand, each of us has its own role."

I was quick to respond: "Your Highness, when people are starving, they are not interested in being taught how to fish. If we give them fishlings for their pond, they will eat it, rather using them for breeding. Our organisation gives people the fish, so they are not starving anymore, and have the energy to be taught how to fish, and to fish themselves. Other organisations we work closely with, teach them how to fish, how to breed fishlings. After that, others come in and teach them not to overfish their pond, or even to market their excess harvest, set up funding mechanisms to sell their harvest beyond their own village. We all work hand in hand, each of us has its own role."

How true are we to our aid commitments?

This was then. But at this moment, there is a growing concern and dissatisfaction in the aid world. How well have we done in the past decades. Have we really followed our own reasonings and explanations..? Or were they mere justifications for our own existence?

The global food crisis hitting the poorest people first, is an objective proof we - the international aid community - have not done well enough. Have we - all of us - not concentrated too much on giving people fish, rather than teaching them how to be independent from foreign aid? How much of it could have been avoided? How can we learn from our lessons?

While the international focus is on the global food crisis, it is the right time to highlight the importance of not only concentrating on short term solutions. Short term solutions for hunger are like drops of water on a hot plate. Let's give people fish, but also concentrate on "teaching them how to fish".

In the context of the global food crisis, this means concentrating not only on emergency food aid, but also on achieving sustainable food security and reducing poverty in developing countries through non-for-profit and transparent scientific research in the fields of agriculture, forestry, fisheries, policy, and environment.

I explicitly exclude the agricultural research done by the likes of Monsanto and Cargill, international commercial giants who only aim at increasing their profit margin, often to the detriment of the farmers in poorer countries.

Let's rather have a look at the benevolent work of organisations like the CGIAR, the Consultative Group on International Agricultural Research.

Agricultural aid research, a proven success.

The CGIAR has a proven success track record (Source): - Successful biological control of the cassava mealybug and green mite, both devastating pests of a root crop that is vital for food security in sub-Saharan Africa. The economic benefits of this work are estimated at more than $4 billion.

- Successful biological control of the cassava mealybug and green mite, both devastating pests of a root crop that is vital for food security in sub-Saharan Africa. The economic benefits of this work are estimated at more than $4 billion.

- Increasing smallholder dairy production in Kenya improving childhood nutrition while generating jobs. This award-winning project with smallholder dairies has contributed up to 80 percent of the milk products sold in the country. - New rice varieties for Africa, which combine the high yields of Asian rice with African rice’s resistance to local pests and diseases. Currently sown on 200,000 hectares in upland areas, they are helping reduce national rice import bills and generating higher incomes in rural communities.

- New rice varieties for Africa, which combine the high yields of Asian rice with African rice’s resistance to local pests and diseases. Currently sown on 200,000 hectares in upland areas, they are helping reduce national rice import bills and generating higher incomes in rural communities.

- An agroforestry system called “fertilizer tree fallows,” which renews soil fertility in Southern Africa, adopted by than 66,000 farmers in Zambia.

- Widespread adoption of resource-conserving “zero-till” technology in the vital rice-wheat systems of South Asia. Employed by close to a half million farmers on more than 3.2 million hectares, this technology has generated benefits estimated at US$147 million through higher crop yields, lower production costs and savings in water and energy. - A flood-tolerant version of a rice variety grown on six million hectares in Bangladesh. The new variety enables farmers to obtain yields two to three times those of the non-tolerant version under prolonged submergence of rice crops, a situation that will become more common as a result of climate change.

- A flood-tolerant version of a rice variety grown on six million hectares in Bangladesh. The new variety enables farmers to obtain yields two to three times those of the non-tolerant version under prolonged submergence of rice crops, a situation that will become more common as a result of climate change.

- A new method for detecting and reducing by 100% aflatoxin, a deadly poison that infects crops, making them unfit for local consumption or export benefiting farmers throughout sub-Saharan Africa.

- More than 50 varieties of recently developed drought-tolerant maize varieties being grown on a total of about one million hectares across eastern and southern Africa

- A simple methodology for integrating agriculture with aquaculture to bolster income and food supplies in areas of southern Africa where the agricultural labor force has been devastated by HIV/AIDS, doubling the income of 1,200 households in Malawi.

- Etcetera, etcetera, etcetera....

Digging our own grave.

All good news. Except that the focus on emergency food aid seems to have drawn worldwide attention - and funding - away from long term agricultural research. Proof of the matter is that while U.S. President George W. Bush recently ordered up $200 million in emergency food aid, with a follow-up of another $755 million, the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) is cutting as much as 75% of their funding to the CGIAR (See Science Magazine). USAID's support to the CGIAR in 2006 was $56 million or about 12% of the CGIAR’s core budget.

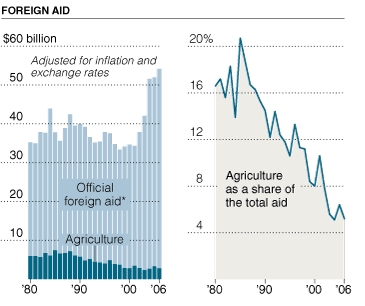

And USAID is not the only one to blame. Look at this graph illustrating the worldwide trend of foreign aid (which excludes relief aid - as the graph would then look even worse!) going up, versus the downward trend of in agricultural aid.

Here is another interesting graph, comparing the annual budget of the International Rice Research Institute (IRRI), one of the CGIAR's research centers, and the global rice stock pile volume, using the latter as a measure for consumption versus demand on rice. Now is there not a strange correlation to be noticed? This can not be coincidence.

How a small bug illustrates a worldwide problem

Talking about the IRRI, here is an example of how, by cutting back transparent and not-for-profit agricultural research is as bad as digging one's own grave:

The brown plant hopper, an insect no bigger than a gnat, is multiplying by the billions and chewing through rice paddies in East Asia, threatening the diets of many poor people. China, the world’s biggest rice producer, announced on May 7 that it was struggling to control the rapid spread of the insects there. A plant hopper outbreak can destroy 20 percent of a harvest.

The brown plant hopper, an insect no bigger than a gnat, is multiplying by the billions and chewing through rice paddies in East Asia, threatening the diets of many poor people. China, the world’s biggest rice producer, announced on May 7 that it was struggling to control the rapid spread of the insects there. A plant hopper outbreak can destroy 20 percent of a harvest.The damage to rice crops, occurring at a time of scarcity and high prices, could have been prevented. Researchers at the International Rice Research Institute say that they know how to create rice varieties resistant to the insects but that budget cuts have prevented them from doing so. (Full)

Learning from the past

In the 1960s, population growth was far outrunning food production, threatening famine in many poor countries. Wealthier nations joined forces with the poor countries to improve crop yields. Yields soared, and by the 1980s, the threat of starvation had receded in most of the world. With Europe and the United States offering their farmers heavy subsidies that encouraged production, grain became abundant worldwide, and prices fell.

Many poor countries, instead of developing their own agriculture, turned to the world market to buy cheap rice and wheat. In 1986, Agriculture Secretary John Block called the idea of developing countries feeding themselves “an anachronism from a bygone era,” saying they should "just buy American". (Full)

And this attitude got the world into the mess it is in today: a demand (the world population) outgrowing the supply (food production)... The below graph clearly illustrates this trend (the food production - in purple- is represented by the total production of grain in the world).

Bottomline. And how you can help.

We need to push the international community for long-term agricultural research aiming solely at making developing countries food self-sufficient, without any commercial interests at heart, if we want to resolve this food crisis and avoid it from ever happening again.

Here is one way how you can help: sign the petition urging USAID to maintain its support for the CGIAR's food research centers.

Maybe, just maybe, we will be in time to turn this food crisis, into an opportunity, and really teach people how to fish, rather than just giving them fish to eat. Maybe, just maybe queues for food hand-outs in developing countries could be a thing of a past.

More articles on The Road about the global food crisis

With thanks to "the other E" for the inspiration!

Graphs courtesy New York Times and planettoughts.org.

Pictures courtesy Luis Liwanag (The New York Times), EPA (Al Jazeera), Crispin Hughes (WFP), CGIAR and Pavel Rahman (AP Photo)

Peter. Flemish, European, aid worker, expeditioner, sailor, traveller, husband, father, friend, nutcase. Not necessarily in that order.

Peter. Flemish, European, aid worker, expeditioner, sailor, traveller, husband, father, friend, nutcase. Not necessarily in that order.

1 comments:

That's the best choice, teaching them "how to fish". Teaching to grow up with their country in a profitable and sustainable way.

Post a Comment