The Man With the Air Conditioner on his Head, Shot at Us

One fine day. Uganda. 1997.

One fine day. Uganda. 1997.‘Just for your information’, says Lionel on his mobile phone from Brazzaville.. On the other side of the line, in Kampala, Uganda, I smile. I love Lionel. His French accent seeps through his English.

“Just for your information, I drove back from the airport a few minutes ago. Dropped off one of our staff. On the way back, I saw some troops on the street. There was machine gunfire here and there. Not much, but it does not seem normal. I am going back to the hotel, and will let you know what’s happening.”

As I put the phone down, I look at Mats, sitting at his desk on my left. We have an open space office. No walls, so everyone can see everyone else. And hear everyone else. Mats puts his chin up, and smiles as if saying “And… what news from Lionel?”.

“Dunno… Gunfire in Brazzaville town. He’s going back to his hotel.”

Through the years in this ‘humanitarian business’, Lionel developed a sixth sense for danger. Like many of us. I don’t doubt his judgment. He is often right. Even though the circumstances do not really confirm his sensing: Congo – to avoid confusion with the Democratic Republic of Congo, we call it Congo Brazzaville -, has been quite stable since many years. Even through the democratic elections five years ago, where the new president, Lissouba, was elected after 28 years of one-party rule of strongman Sassou-Nguesso.

Lionel calls me every day. He is blocked in the hotel. What initially looked like sporadic gunfire developed into a full scale civil war. Brazzaville was up in flames as the former dictator Sassou-Nguesso and his Cobra militia, backed up by mercenaries and the Angola army, tried to oust the government. The French paratroopers stationed on the outskirts of the city had secured the hotel which was now the camping place for all expatriates who fled their homes and businesses. A week or so later, all drive to the airport in a convoy and again under the protection of the French paratroopers, get evacuated.

Lionel calls me every day. He is blocked in the hotel. What initially looked like sporadic gunfire developed into a full scale civil war. Brazzaville was up in flames as the former dictator Sassou-Nguesso and his Cobra militia, backed up by mercenaries and the Angola army, tried to oust the government. The French paratroopers stationed on the outskirts of the city had secured the hotel which was now the camping place for all expatriates who fled their homes and businesses. A week or so later, all drive to the airport in a convoy and again under the protection of the French paratroopers, get evacuated.Since then, we heard little news other than what we see on CNN and BBC World.. Brazzaville burns. Angolan MIG fighter planes fly over the city and seem to drop bombs randomly over the city center. Several competing militia control different parts of Brazzaville, looting, burning and raping. What seemed a stable country one day, is burnt to ashes in a civil war, the next day. How many times have we not seen this, especially in Africa? The victims in the end, are still the ‘ordinary people’. When there is an armed conflict, the –often already weak- economy comes to a standstill. Schools close. Hospitals are burnt down. Shops are looted. Fields, lush with abundant green crops, are left unattended and rot, leaving behind a starving population.

Four weeks later, in a ferry crossing the Congo River.

The ferryboat is cramped with Congolese, who fled the fighting a few weeks ago and now try to go back home. We find a spot on the upper deck, looking at Kinshasa on one side of the Congo river, and Brazzaville on the other. We were safe in Kinshasa, but crossing a river, just a few

miles wide, will bring us in a totally different world. Kinshasa behind us was buzzing with activity, as it always is. But looking ahead, we don’t see much movement in Brazzaville, apart from the plumes of smoke raising slowly.

miles wide, will bring us in a totally different world. Kinshasa behind us was buzzing with activity, as it always is. But looking ahead, we don’t see much movement in Brazzaville, apart from the plumes of smoke raising slowly.We received security clearance for twelve hours to go to our -probably looted- office, save whatever equipment we can save, and set up a new office within the compound of Unicef, in the center of town. Mats and I are one of the first foreigners to enter the city after the civil war. God knows what we will find… Missions like these are always interesting, get the adrenaline pumping, but at the same time, we are aware of the dangers. The swollen cadavers floating by on the water, certainly remind us of it.

At the ferry docks, one crowd tries to get onto the ferry before the other crowd could step off, resulting in a massive whirl of people, wooden crates with chickens, huge stacks of clothes, suitcases and bags. Kids loose their mums and start crying, women start shouting. Here and there some guys get punched on the nose. When we finally get off, a guy comes to us, wearing a blue UN helmet, a flack jacket with “UN Security” in big letters and on old Kalashnikov in his hand. He indicates us to follow him, but does not say a word. A car is waiting, with a local driver. Big UN marks on the side and a while flag in front.

As we drive on the road to town, we pass the crowd which just got off the ferry, and then… not a living soul anymore.

A ghost town. And a guy with an air conditioner on his head.

A ghost town. And a guy with an air conditioner on his head.There are no other words to describe what we see as we drive slowly through the streets of Brazzaville, other than “A ghost town”. The streets are empty of anything alive. Trash everywhere. Bricks, steel pipes, burnt machinery, carcasses of cars. The doors of the buildings

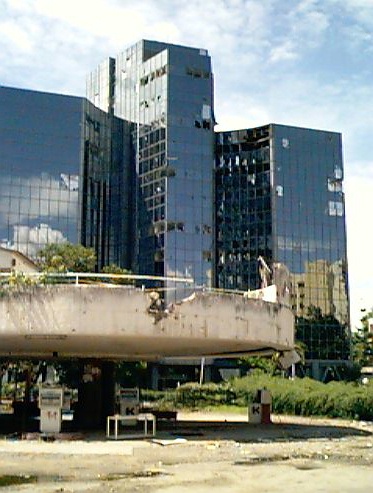

are forced open. Most windows are broken, marked with black traces of soot. All buildings are empty. Completely empty. It looks like the looting was pretty thorough. Everything that could be removed, seemed to be removed.. The car stops at a big crossroad in the center of town. This is typically a spot where militia would fight for the control, so they can ask bribes from the drivers trying to get through or block the movement of other fighting parties. A tall building stands in silence in front of us. I guess it was a hotel up to a few weeks ago. The outside surface is covered with mirror glass, most of it broken. Curtains swing out of the windows and move slightly in the wind. There are bullet holes and traces of impacts from grenades all over the walls of what once was a fancy hotel entrance.

are forced open. Most windows are broken, marked with black traces of soot. All buildings are empty. Completely empty. It looks like the looting was pretty thorough. Everything that could be removed, seemed to be removed.. The car stops at a big crossroad in the center of town. This is typically a spot where militia would fight for the control, so they can ask bribes from the drivers trying to get through or block the movement of other fighting parties. A tall building stands in silence in front of us. I guess it was a hotel up to a few weeks ago. The outside surface is covered with mirror glass, most of it broken. Curtains swing out of the windows and move slightly in the wind. There are bullet holes and traces of impacts from grenades all over the walls of what once was a fancy hotel entrance.We open the car windows a bit to listen for gunfire. There is none close by, but we clearly hear some shots being fired from an automatic rifle quite a bit further away. It is answered by a rakarakaraka of a machine gun. Only for a few seconds, and then silence again.

We drive forward slowly, and branch into one of the main avenues. Silence. Nothing but the soft crackling sound of our tires crashing broken glass scattered on the road. I hope we don’t get a flat tire. Would not want to get out of the car at this moment.

All of a sudden, a guy comes running from a small side street. He wears ragged camouflage pants. His naked upper body gleams with sweat. He carries a big air conditioner on his head, wires dangling off his back. We hit the brakes and stop. For a second, he looks at us with wild eyes. We look at him. In a flash, one of his hands lets go of the aircon, and we see him grab a machine gun slung over his shoulder. The driver hits the gas pedal as the looter turns towards us, raising his gun with one hand, still holding on to the air conditioner with the other. We speed into a side street, while we hear the crackling gun fire of the Kalashnikov. We don’t look back, and keep on driving. The bullets did not hit us. Maybe he just shot in the air to scare us.

After half an hour, we arrive in our office. Well, what remains of it. In the building, we have to climb over heaps of papers, smashed furniture and curtain rags spread over the ground. Everything of value is gone. No trace anymore of the equipment Lionel has installed a few weeks ago. Through a hatch, Mats and I climb onto the roof. The antennae and the mast is still there. We carefully shuffle over the corrugated panels and take the mast down. Single gunshots in a distance. Each time, instinctively, I pull my head down. It is an awkward sound. Absolute silence, and then a gunshot. And then nothing anymore.

I can not hear you, the shooting is too loud!

In the afternoon, we install the equipment we brought from Kinshasa in the UNICEF office

compound. As by a miracle, their compound was left intact. It even has electricity from a generator. We brief the staff on the use of the newly kitted equipment and go back to the car, parked inside the compound, next to the fence made of 3 meter high rusted thin corrugated plates. We call our Kinshasa office over the car’s radio, to tell them we are about to wrap up, and will be making our way back to the ferry soon. Suddenly, we hear voices on the street, right outside of the fence, just two meters away from where we are sitting in the car, talking on the radio. We turn down the volume of the radio, as the voices of several men on the other side of the fence gets louder. We hear the crickcrack of a gun being loaded. There is banging on the corrugated fence. Someone is being smashed against it. It is as if we are sitting right next to the skirmish. And we are, just separated by the thin fence. One voice starts crying fanatically, as in panic. Pleading. The other voices keep pounding. Someone laughs. Several machine guns crackle, and then there is silence again. Some mumbling. The sound of something being dragged away. And then.. nothing anymore…

compound. As by a miracle, their compound was left intact. It even has electricity from a generator. We brief the staff on the use of the newly kitted equipment and go back to the car, parked inside the compound, next to the fence made of 3 meter high rusted thin corrugated plates. We call our Kinshasa office over the car’s radio, to tell them we are about to wrap up, and will be making our way back to the ferry soon. Suddenly, we hear voices on the street, right outside of the fence, just two meters away from where we are sitting in the car, talking on the radio. We turn down the volume of the radio, as the voices of several men on the other side of the fence gets louder. We hear the crickcrack of a gun being loaded. There is banging on the corrugated fence. Someone is being smashed against it. It is as if we are sitting right next to the skirmish. And we are, just separated by the thin fence. One voice starts crying fanatically, as in panic. Pleading. The other voices keep pounding. Someone laughs. Several machine guns crackle, and then there is silence again. Some mumbling. The sound of something being dragged away. And then.. nothing anymore…It all happened in less than a minute. Mats and I are still sitting in the car. We have not moved an inch. Mats still holds the microphone close to his mouth, as when he interrupted his radio conversation, just a minute ago. During that minute, a corrugated fence of just a few millimeters thick, had separated life from death. Those that were fortunate enough to continue living, and those who were not.

This time, we were lucky. We were at the right side of the fence. Once again. I wonder ‘when our luck is going to run out?’. When are we going to be at the wrong side of the fence?

Postscriptum: six years later.

We –Tine, the kids, me - are driving back to Belgium from our skiing holiday in Italy. We just pulled off the highway, on the outskirts of Luxembourg, to get gas. As I put the nozzle into the tank, my mobile phone rings. It is Arthur. On mission in Brazzaville together with Karen.

“I know you are on holiday, but Mats in Dubai is busy on the phone with the guys in Iran. Just to let you know the mobile phone network over here in Brazzaville goes up and down. And there is some shooting in town. We were supposed to fly out tonight, but we’re not risking to drive to the airport. We are staying put in the hotel. Just for your information…”

Somewhere history repeats itself. And it will continue repeating itself, probably until the world learns from its mistakes.

Top picture: copyright Reuters, picture evacuation courtesy L.Marre

Continue reading The Road to the Horizon's Ebook, jump to the Reader's Digest of The Road.

Peter. Flemish, European, aid worker, expeditioner, sailor, traveller, husband, father, friend, nutcase. Not necessarily in that order.

Peter. Flemish, European, aid worker, expeditioner, sailor, traveller, husband, father, friend, nutcase. Not necessarily in that order.

1 comments:

Great read. Lived in Kinshasa in 2000 and 2003. Thanks

Post a Comment