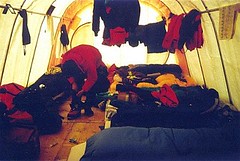

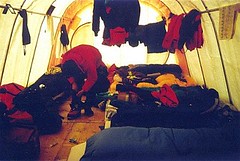

I kind of wake up. I don’t really want to wake up. I just want to sleep. My body and mind are tired. Tired of days on end working, battling against the snow, wind, cold. Fresh snow slips through the small opening I make in my sleeping bag, trying to take a peek at the inside of the tent. I see the dim light through the tent cover, but that is no indication of time. It is always light this time of the year on the Antarctic. My watch tells me it is 5 o’clock. I have to think a while if that would be 5 AM or 5 PM.. Hmmm, AM it is. Soon my shift will start. I have to get up, but my body refuses. I stare at the side of the tent.

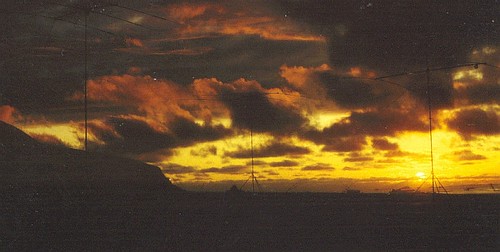

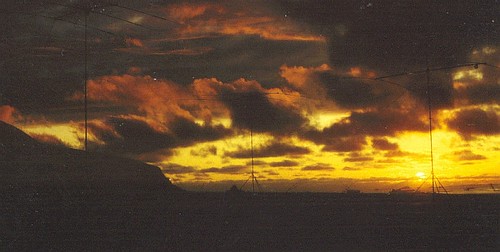

The storm started yesterday evening, and is still blowing in full force. It pushes and pulls violently on the sides of our Weatherhaven tents as if it is trying to get rid of it. The thick nylon cargo lashes we pulled over the tents vibrate in the wind as if they were huge strings. The storm howls and roars as if it were nature’s way to say “you guys don’t belong here”. It is true, we don’t belong here. It has only been 60 years since the first people set foot on this godforsaken island near the Southpole. There have been more people on the moon than here, on Peter I island. People should not be here. Living creatures don’t belong here. This is a land of ice, an Antarctic desert.

I pull one hand out of the sleeping bag and brush off the fresh layer of snow which was blown into the tent. No matter how much we tightened the tent cover, the snow always finds a way in. The two meter high half-cylindrical frames move with each new violent pull from the storm. Most of our clothing hangs lined up on cloth hangers. They swing slowly on the frames. It looks

like a line-up at the dry cleaners… We are far away from the nearest dry cleaner. Apart from our group of nine expeditioners, we are more than one thousand miles away from other human beings… I pull myself up, and sit on my cod. It is freezing. Must be minus five or ten degrees Centrigrade inside the tent. We don’t dare to light the heater anymore, after the small fire we had a few nights ago. Shivering, I unzip my thick thermal underwear, and put on several layers of polar fleeces, thermal longjohns, and then the Goretex outerwear, thick socks and my leather boots, a cap and a hat, ski goggles and two layers of gloves. There is no part of my body uncovered. With the wind blowing that hard, the windchill drops the temperature down to minus 80 Centigrade outside. Any uncovered piece of skin freezes in no time. A few days ago, we had problems with one of the radio antenna masts. Trying to fix some bolts, I was stupied enough to pull off my gloves so I could fit the nuts onto the bolts. I grabbed hold of the mast with my bare hand and instantly, my skin frooze to the mast. It took three of us breathing onto my hand to melt it off the damned metal.

Willy gets dressed too. Our shift is about to start. A new day is born. The morning shift goes to work. Well almost, as the outer zipper from our tent cover is froozen. I can’t use my lighter as it would melt the plastic. Willy pulls some bags of active carbon from his pocket, shakes it to get it heated up, and holds it against the zipper to warm it up. It takes at least half an hour to move the zipper half a meter. As by miracle, all of a sudden, with a firm pull, the damned cover unzips, and a wall of snow falls into the tent. We are too tired to curse. We know this can happen. Our life here consists mostly of battling against the wind and the snow. The only thing we can see through the half-open tent cover, is a wall of snow. It must be at least three meters high. Trying

not to spill too much of it into the tent, we delve into it, trying to get out. The snow is soft and provides no grip. We have to firm it up by kicking it with our boots. We can only “feel” we are out, but can not “see” anything to confirm it. The wind bites us in the face. Everything is dim grey-whitish in the faint light. Visibility is nil. Totally nil. Ziltch. The snow beneath us, the snow blown up by the howling wind, the sky, all white.

On our belly, we pull ourselves up, and slide down the snowpile which has formed around our tent. When I stand up, I sink up to my waist into the snow. It is light. The snow below is almost as air, so thin, so… well air-y. Walking is almost impossible. We wade through the snow. With some efforts, but at the same time, everything around us is almost psychedelic, making us numb of any physical feeling. This is what they call a white-out. The snow below, the snow blow up by the storm, the air, the ground. Everything has the same shade of white. I tumble over my own feet, and fall. But it is even hard to tell that I fell. There almost no difference in the density of the snow in the air and the snow on the ground. I fall like onto an airy cushion of white. My goggles get covered up, and my own breath sets moister onto it. Makes it even more difficult to see anything. I am floating. A light gaiety wraps around me, I laugh. I am floating. Unaware if I am laying down or standing up. Am I feeling the resistance of the snow on the ground, or the resistance of the wind pushing onto my body? The layer upon layer of special clothing keeps my body warm, makes a protective shell around me, making me even less aware of my surroundings. I float. I laugh. I am flying. Gliding through the whiteness. I could be meters up in the sky, or just wading through snow, I do not know. I.. I just float. Without knowing, I become desorientated. There is no trace of any of the crates we have stacked around our tents, nor of the cables. I see no tents, not even shades of them. Through the howling of the wind, I still hear the faint noise of the generators, and turn my head trying to find a bearing, purely on the noise, but the wind disperses even that. Even the noise comes from everywhere. This is surreel. A dream.

I start walking, wading through the snow to what I think is the direction of the kitchen tent. A dozen yards further, someone pulls me from the back. Willy. He pulls my head close to his mouth, and shouts ‘Are you nuts? Where are you going to?’. I can hardly hear his voice through the storm. I stretch my arm to give an indication of where I am going, but Willy waves his hand. ‘No! It is that way, come’. By myself, I had wondered a hundred meters from the camp, straight into the area we know is full of crevasses. If Willy had not stopped me, I might have disappeared. Nobody would have found me in time. And I would not have been able to get out by myself, tumbling down ten, maybe a hundred meters down the ice caves of the glacier we put our camp on.

Hand in hand, Willy and I make our way to one of the generators. In our efforts to keep them ice and snow free, we tried everything. Our latest experiment was to build a wall of crates around them, but still the snow getss into the sheltered hole. Luckily as we keep the engines running, their heat melts off anything. The disadvantage is that the heat also has the generators dig

themselves into the snow. The glacier is hundreds of meters thick here, so they still have some way before they literally hit rock bottom. The disadvantage though is that it makes a hell of a challenge trying to service them, or fill them up with gas. I crawl over the wall of crates and jump into the hole. Willy hands me the jerry cans, and I flip the lid open, put the funnel into the generator’s gas tank and pour the gas in it. The wind sprays the fuel all over my legs, and hands. I can smell the fumes. I have to be careful as the generator is hot. If I spill too much, the whole thing will go off in flames. Willy crawls into the hole and makes a joint between the jerry can’s lid and the gas tank. “Pour!”, he shouts, trying to lift his voice above the wind and the deafening noise of the generator. And I pour. Thinking how much I hate this ‘morning duty’ to refill the gensets. And this is only one. We have four of them. But still, I love it. I love this challenge. I love to find my own limitations, I love to face my own fear and laugh at it, in the face. I love doing this, this expedition, that people said to be impossible. I love to laugh in their face. Even as a new blow of wind sprays fuel all over me.

An hour later, we unzip the opening of the working tent. In the small space of 2.5 by 2.5 meters, three guys are sitting, working on the radio. They have the gas heater on, and are sweating in their Tshirt. They are concentrated trying to decypher the radio messages, and only look up at the distraction of two people crawling into their oasis of heat. Willy and I look alike. All covered up with patches of froozen snow, mucus dangling off our nose, damped ski goggles and smelling like we fell in a petrol pump. We pull off our caps and goggles, and smile at our team mates. “Goooooood moooooooooooorninggggg Vietnaaaaaaaaaaaaam!”, we laugh… A new day is born on Peter I. The most isolated island in the world. How we love this life.

Continue reading The Road to the Horizon's Ebook, jump to

the Reader's Digest of The Road.

Read the full post...

The story was written with the bombing of the Canal Hotel, the UN HQ in Baghdad, on August 19 2003 as the center part. That day still represents a very very dark period for me. A day I lost M, a close friend, due to senseless violence she had no part in. A day I lost several of my colleagues, and where several people in my team got severely wounded. A day which scarred many of us even up today.

The story was written with the bombing of the Canal Hotel, the UN HQ in Baghdad, on August 19 2003 as the center part. That day still represents a very very dark period for me. A day I lost M, a close friend, due to senseless violence she had no part in. A day I lost several of my colleagues, and where several people in my team got severely wounded. A day which scarred many of us even up today. With Sergio Vieira de Mello's cruel disappearance, the world has not only lost a brilliant and charismatic advocate of peace and human rights but also a tireless and highly effective humanitarian champion.He represented the best the UN could offer in terms of promoting multilateral solutions to today's world's most challenging situations. He remains a sterling example of selfless service for many to emulate.

With Sergio Vieira de Mello's cruel disappearance, the world has not only lost a brilliant and charismatic advocate of peace and human rights but also a tireless and highly effective humanitarian champion.He represented the best the UN could offer in terms of promoting multilateral solutions to today's world's most challenging situations. He remains a sterling example of selfless service for many to emulate.

This does not look bad, but once those axles rest on the sand, there is only one thing to do: start digging, or towing!

This does not look bad, but once those axles rest on the sand, there is only one thing to do: start digging, or towing!

This one was more unfortunate... It got in too deep and the water washed it away.

This one was more unfortunate... It got in too deep and the water washed it away.

Peter. Flemish, European, aid worker, expeditioner, sailor, traveller, husband, father, friend, nutcase. Not necessarily in that order.

Peter. Flemish, European, aid worker, expeditioner, sailor, traveller, husband, father, friend, nutcase. Not necessarily in that order.

The Road's Dashboard

Log in

New

Edit

Customize

Dashboard